Image via Wikipedia

Traditionally in Italy one says buon appetito! before beginning to eat a meal. This courteous wish for one to enjoy their meal can be literally translated to mean “have a good appetite.” But even if you aren’t hungry, you’re guaranteed to enjoy the dishes before you. This is because Italian food is prepared to be both delizioso to the mouth and appealing to the eye. (In fact there’s a famous saying about food and its presentation: anche l’occhio ha la sua parte! Food is not just for the stomach, but for the eye as well!)

Two of the hallmarks of Italian cuisine are elegant simplicity and high quality. Regardless of location, the freshest ingredients are prepared in such a way as to retain their natural qualities, especially appearance and fresh, distinctive taste. This means that the cooking techniques are usually very simple, and preparation time is relatively short.

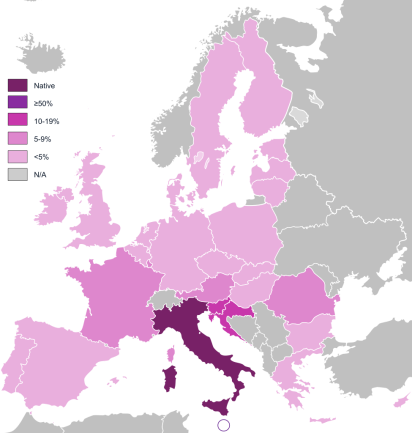

Because of the country’s location and history, the cuisine varies dramatically from north to south, east to west. For example, the cuisine of the north is characterized by less use of tomato sauces, pasta, and olive oil, because these types of ingredients do not grow well locally (they need more heat and sun) and there is a strong influence from other countries, like France, which have their own distinctive culinary traditions. So northern dishes use more cream-based sauces (which means more butter, cheeses, or lard in the recipes), and rice or corn. In the north you will therefore find that the majority of primi piatti are not la pasta but rather il risotto and la polenta. And many main dishes– i secondi piatti— feature the diverse wild game found in the plains and mountainous regions of nord Italia. To find out more about northern Italian cuisine, click here.

L’Italia centrale is the part of the peninsula that has provided what the rest of the world considers “real” Italian food: cured meats like il prosciutto, sumptuous olio d’oliva, rich, intensely flavored cheeses like il parmiggiano-reggiano, and fresh, brightly flavored sughi al pomodoro (tomato sauces). For secondi piatti one finds either locally caught seafood in the coastal regions on both the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas, or simple but savory beef dishes, such as the world-famous bistecca alla fiorentina. Exploring the culinary cuore (heart) of Italy is a treat, so click here.

L’Italia del sud is renowned for its excellent crops of durum wheat– the essential ingredient of such popular dishes as pizza, foccaccia, and countless varieties of dried and fresh pasta (there are over 165 documented; to find out the various forme— types– click here. Also check out the national pasta museum in Rome). The best olive oil and tomatoes come from southern Italy, because of its abundant sun and unique soils, with the rugged terrain providing a home for flock of sheep and goats, which provide both meat and milk (for cheeses) in a variety of dishes. Since so much of southern Italy is surrounded by water, i frutti di mare (literally fruits of the sea; seafood) play an important role, with anchovies, clams, mussels, tuna, sea urchins, and shrimp being particularly prominent.

The ancient Greeks settled in Sicily and southern Italy, and so there are many Greek influences in the local cuisine. Sicily also had a strong Arab presence for many centuries, so “exotic” spices such as pepper, saffron, clove, cinnamon, and nutmeg are often added to sauces and desserts. Lamb, goat, rabbit, goose, and turkey are popular in main courses, and in the desserts one can find many of the south’s famous agrumi— citrus fruits such as oranges and lemons– as well as pistachio and sugar cane, which were all also introduced to the region by the Arabs. Not surprisingly, la Sicilia is famous for its rich, complex sweets, ice creams and pastries.

Taking a totally different direction, southern Italy’s other large island– la Sardegna-– is known for its hardy but austere cuisine. Seafood abounds in the coastal areas (the aragosta— lobster– is so famous that Europeans fly to the island just to eat it fresh), but the real cucina sarda is represented by the rugged, mountainous spine of the island, where Sardinian shepherds watch their flocks from neolithic nuraghi (Stone Age ruins) and farmers fight with the harsh conditions to produce heavy, robust wines and intensely flavored produce, like cactus pears, artichokes, zucchini, and more. Roast suckling pig (la porchetta), lamb, and goat are the main meats, and a bewildering array of home-made breads— some so thin that they’re called carta di musica (sheet music) and others so ornately formed and decorated that they are proudly displayed in churches and holiday parades– are other staples of this simple island fare. A virtual trip to the cuisine of l’Italia del sud — also known as il Mezzogiorno (land of the noonday sun) can be found by clicking here.

For an overview of general similarities and some regional differences, with links to each region and cuisine summaries, click here.

ITAL 1 Students: Explore the cuisine of your Italian family’s regions by clicking on the appropriate links. Copy and bring to class at least one recipe from each region– selecting them from different courses (i.e., l’antipasto, il primo piatto, il secondo, il contorno, il dolce, ecc.)– so that your group can begin to develop a possible menu tradizionale for the course final’s festa in piazza.